Val Gielgud and How to Write Radio Plays:

The Wireless Play - 6 Articles

The writing in these articles could not be described as consistent and it should be borne in mind that they were written by a busy productions executive marshaling a new role as well as managing a complex and demanding centre of creativity and live performance. Key points are extrapolated and then illustrated by what Gielgud himself describes as key or landmark productions in the year. Reference is also made to productions which are not necessarily discussed by Gielgud but certainly had a significant impact.

Article 1 was published on page 397 for the issue of May 24, 1929. It can be argued that many of the points he makes resonate as the advice and creative cultural imperatives for BBC Radio Drama up until the present day. The points made throughout the series also set out the parameters of limited 'praxis' philosophy attending radio drama as an artform. It is argued that certainly within the United Kingdom little progress has been made understanding and communicating the potential of irony, narratology and story telling philosophy which might be unique to audio play.

The Wireless Play - I. For The Aspiring Dramatist

a: Dramatists should study the medium with ‘special care’.

b: Stop regarding radio as a Cinderella Medium for writing. It is not in its experimental stage and does not have to justify itself.

c: There are no great financial profits for the writer, but it should be professionally remunerated.

d: As with any writing medium you need to be practical. 50 cast members and 7 acts is unrealistic. Do not waste time writing plays that ‘are hopelessly incapable of performance.’

e: In 1929 Productions Department at Savoy Hill received on average 25 plays a week. Of every 100 plays received only 2 complied with ‘the special conditions for their claims to be seriously considered for production.'

f: ‘Ignore Stage Technique’.

g: Scotch the idea that ‘the microphone' is a poor substitute for the real theatre and 'therefore bad art’. Gielgud said: ‘The time is over for this curious assertion that the broadcast play is the blind Cinderella of the drama’.

h: It is different. Radio is not a nursery slope or practice run for stage, television or film.

i: Common ground does exist:- the ability to write good, witty or forceful dialogue is born, not made. Both stage and radio play need ‘the ability to write’.

j: It may be easier to cover bad writing in the theatre with spectacle, good looks, pretty clothes, ingenuity of production - ‘Not so with the radio play’.

k: Radio Drama has been absolutely divorced from Stage Drama. Gone are the days when ‘a microphone might be put into a theatre to broadcast a play from the stage’. His prophesy here was not exactly confirmed by experience. As recently as 1995 the BBC mistakenly thought a live stage production could constitute credible radio drama listening. (p 255, Crook, T (1999) Radio Drama- Theory & Practice, London, New York: Routledge.

l: Film broke away and made its own art-form because there was no sound. In 1929 the advent of the Talkies, there was a need to ‘break away’ from the limitations inseparable from the stage.

Coinciding with his first two articles were two highly critical letters published in the 'What the Other Listener Thinks' column that have all the hallmarks of Gielgud 'faking' controversial points to generate debate and support aspects of his policy and agenda.

May 31st 1929.

'From time to time the BBC complain that writers do not appreciate the art of the radio drama, that too few suitable plays are submitted to them and so on. Setting aside the question of remuneration, let us consider what the BBC does to encourage embryo radio dramatists. Perchance the young writer will start with a one-act comedy, which will take at least five hours to write out and type, in addition to time and labour involved in planning it out. The odds are that this first born is returned with a circular, saying that it has received careful consideration , but is not quite suitable for broadcast purposes; not a word of advice or encouragement. As the play has been written especially for broadcasting, it is practically useless submitting it to any other market, and the young author’s hopes are summarily shattered. Half a dozen words of encouragement might be the means of discovering a Shakespeare of the ether - Yours Disgruntled.'

A reason for arguing that Gielgud could have been the author is that it matches his concern about the low level of remuneration for writers. He was fond of referring to Dr Samuel Johnson's dictum that only a blockhead would write for anything except money. (p xv Gielgud, V (1946) Radio Theatre - Plays specially Written for Broadcasting, London: MacDonald & Co.)

June 28th 1929.

Might I make two simple suggestions about broadcast plays? Firstly, that as the actors are not seen, the characters should be few; otherwise the effort to distinguish the voices destroys the pleasure of listening. This is quite different in the theatre, where the action is seen. Secondly, that broadcast plays should, as a rule, be short. This is not realized yet, to judge by words quoted from The Radio Times of June 7: ‘The listening audience has not yet acquired the automatic habit of listening to radio plays as they have the habit of watching a play in the theatre.’ Why? The answer is in the last three words. When we go to the theatre we take ‘time off’, and have then nothing to do but enjoy ‘seeing’ and ‘hearing’ for two or three hours. At home, on the contrary, we are liable to interruptions - a caller, letters to be written, etc., children, and the hundred and one things to be done after the ordinary work of the day. So the busy householder likes a short play - Yours V.M.C, Newbury.

The reason for suggesting that Gielgud may have authored this letter is that it draws attention to his article, generates a debate and reemphasizes via another source the need for aspiring writers to consider the special conditions of radio drama listener. It also, like the correspondence from 'Disgruntled', has no actual identifying feature apart from three initials and the town of Newbury in Berkshire which even in 1929 had a sizeable population.

1929 Radio Times illustrations of a 'Hogarthian' view of listening to radio in the home and Broadcasting House in Manchester.(p iv, The Radio Times, December 20, 1929)

Val Gielgud. The Wireless Play - II. Choice of Subject

pp 449 & 550 The Radio Times 31st May 1929.

a: For radio they must ‘appeal to an enormous audience’.

b: Radio ‘is entertainment of modern democracy.’

c: Radio has to be considered as appealing ‘potentially to a far greater number of people’ than cinema.

d: Consider the audience. It is easy ‘for sophisticated and hyper-intelligent people to be funny at the expense of an organisation which has to make allowances for such an apparently demoded thing as family life.’ ‘what people are prepared to accept as entertainment under their own roofs is not the same as that which they are prepared to accept in a music hall or in a theatre’.

e: subjects should be essentially popular.

f: aim at the raw elements of human nature which are common to all of us.

g: There are two subjects at least on which the radio dramatist cannot go wrong: The first is a good story. The kind of story which if read in a book you could not lay down until you had finished it. Writers of tales which take their audience or their readers ‘away from the ordinary incidents of life as it is lived by most of us.’ A good adventure story, convincingly written about entertaining and simultaneously possible characters. The second: Attractive personalities or ‘characters we can believe in’. ‘Characters who, from their essential humanity, convince the audience of their existence and their friendliness; characters who produce a definitely sympathetic and charming atmosphere which makes the development of their circumstances interesting to the audience to whom they are introduced.’

h: The wireless dramatist must borrow from the novelist rather than from the playwright.

i: There is little room for caricature in radio. You need ‘real people living a life that is like the life of your audience’. Radio drama gives space for ‘the play of adventure and the play of human character’.

j: The Play of Musical Life. Music has great potential and the radio musical even more so. ‘To concentrate on listening to pure dialogue is unquestionably a strain.’ ‘Mr Shaw has proved that a master of dialogue can retain our listening attention without any difficulty, but it is without fear of contradiction from Mr Shaw that I assert that there are few Shaws.

k: Use of Music. It is used as background or as linking material to break up the monotony of human voices. However, it would be more interesting to interpolate music as a necessity of subject.

l: The time has come for authors to write microphone plays round subjects rather than to attach subjects rather painfully to microphone plays.

m: It is not a criterion of excellence to ‘use as much complication in its production as possible. ‘The best radio plays are the simplest radio plays.

n: Poetic Drama. The microphone offers great possibilities to the play which is dependent entirely upon the beautiful speaking of beautiful words. This could be the case with work written by poets which can never be staged owing to their lack of any dramatic action. ‘If a new generation of Elizabethans were to arise they would have to write for the microphone and not for the stage.’

But there is no greater pitfall for the would-be dramatist than the poetic play. Gielgud warned: the poetic play to justify itself, and especially to justify itself through the medium of the microphone, must be the work of a poet and not of a "would-be" poet.

The Wireless Play - III. Length And Method

pp 502 & 513 Radio Times June 7th 1929.

1. Keynote- Be Practical! No play, however good, stands its best chance of acceptance for the microphone if presented in a slipshod manner. Pay attention to the requirements of length, treatment etc.

2. Preparing the script. Properly typed on quarto paper rather than ’written in longhand on the backs of brown paper bags’.

3. Sound Effects. Indicate the points at which it is necessary for sound effects to occur. Leave it to the producer 'in cooperation with the person responsible for the noise effects at Savoy Hill, to bring these indications to concrete form.'

4. Question of length? Speed of dialogue in the radio is slightly slower than that taken in the theatre. Average timing of a minute and a half to a page is a ‘very fair average at which to work’.

5. In 1929 Gielgud said the ‘best practical length for a radio play is an hour and a half. I do not mean that this will always be the best length or that it is the ideal length.’ His predecessor R A Jeffrey thought the ideal length of a radio play should not be more than 40 minutes. Gielgud argued that the most important people to be considered by the radio dramatist are: audience.

a: He explained the listeners had not yet acquired ‘the automatic habit of listening to radio plays as they have the automatic habit of watching a play in the theatre’. It can be argued that in the year 2001 the same point can be made, largely because unlike the USA in the 1930s and 40s audio drama has never taken a foothold as a mainstream programming format.

b: Audience interest has to be gripped and once gripped - maintained. Unusually mobile background - continually changing scenes, much incidental music and sensationally noisy sound effects contributed to gripping. Outstanding literary brilliance where dialogue by itself suffices to bind listeners to their headphones is also a key factor in maintaining audience loyalty.

6. The Simpler the Better. Tim Crook during his workshop programme in the 2000 London Radio Playwrights' Festival emphasised the maxim ‘There is so much nobility in simplicity. It is apparent that Val Gielgud in 1929 emphasised the advantages of this maxim. He wanted ‘clarity of treatment‘. Even then there was an active debate about the function of narrative in radio drama with two classes of thought.

a: Retention of narrative as being essential in order to convey a clear understanding of plot development to the audience.

b: Removing the narrative and narrator on the ground that until clarity of plot development can be achieved without these aids the true radio play has not been produced. Gielgud’s position was that there is plenty of room for both classes. He argued persuasively: ‘It is not a fact that narrative is always boring or an inartistic excrescence upon the form of radio drama. Particularly is this the case when a radio play is founded upon a novel. Both ‘Carnival’ and ‘Lord Jim’ owed very much of their success to the skilful insertion of proper passages of narrative drawn from the original books.

Or take the further example of St. Joan, where Mr Shaw’s stage directions, which were read in full, were precisely the same thing as linking narrative.’

Gielgud went on to observe that the adapter of ‘The Prisoner of Zenda’ - his close friend and co-writer of crime thrillers Holt Marvell (Eric Maschwitz) had made a mistake by deliberately avoiding the narrative form. It would have been greatly improved by just a little carefully chosen narrative for the sake of clarity. On the other hand Gielgud cited Tyrone Guthrie’s ‘Squirrel’s Cage’ as a play justifiably without narrative: - ‘written straight for the microphone, and was directed immediately at the listener’s ears without any thought for his other senses, not only did the play no harm, but was an essential factor in its success. ‘Squirrel’s Cage’ was written in such a manner that its meaning and its aims were alive perfectly easy to follow, although the interludes were of a symbolic character, without any purely descriptive linking.’

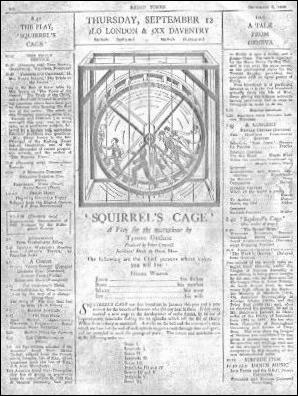

Squirrel's Cage by Tyrone Guthrie was regarded as the most successful play written specifically for the microphone in 1929. It would continue to be revived and generated considerable critical coverage. Alan Bland in the Listener for March 13th 1929 stated that it was 'not only an excellent entertainment but also another important step in the working out of the whole problem of dramatic broadcasting.' Thematically it engaged the issues of the modernist age. However Bland's evaluation of the first performances on March 4th and 6th included the criticism: 'Here and there were lines of the kind we have come to call "theatrical", melodramatic touches which jumped out and marred for a moment the quiet photographic realism... the voices of the chorus were not always so happy.. sometimes the rhythm seemed to flag... nor do I think that the device of the stroke on the gong followed by the screaming rush of a siren, ingenious though it was an idea, really conveyed the sensation of the rush through time and space between scene and scene.' (p 333, The Listener, March 13, 1929)

'Squirrel's Cage' was defined as 'a successful radio expressionist play' and on its repeat in September. On September 6, the Radio Times published an imaginative 'discussion on monotony' entitled 'All The World's A Cage'. A debate ensues between Michael Murray and Robert Herring. The dialogue is a witty and lighthearted promotion of the broadcasts on 2L0 September 12th and 5GB on September 11th.

'Robert Herring: I'm so used to freedom that I'm absolutely captivated by it.' (p 473, Radio Times, September 6, 1929)

7. Gielgud’s advice on narrative to writers:

a: Make up your mind before you begin writing on whether to use it or not.

b: If you do use it you must realise that narrative must be carefully chosen.

c: Narrative passages must not be too long..

d: Narrative passages must be balanced by other characteristics of the play. For example:- if you have considerable passages of linking narrative you must balance them with considerable changes of background, plenty of music and the like.

e: If you prefer to proceed without narrative and adopt ‘the starker technique’ You must take care that you do not become obscure and the essential factors in the development of the plot are not left out or slurred over.

The Wireless Play - IV. 'How Many Studios?'

Page 555, The Radio Times, June 14, 1929.

In the days of Savoy Hill and to a similar extent early Broadcasting House, the BBC used the first 'mixing panel' to combine inputs of performance and sound from different studios. In Germany they tended to record sound in the same large studio. In the USA (at CBS for example) they followed the German model and had components of the production in the same large studio. The BBC technical mechanism was known as 'The Control Panel'. In fact Savoy Hill could mix together input from 6 different studios or locations.

1. '...in radio drama, as in all good art, simplicity is more effective than complication. To use six studios merely, as it were, for the fun of the thing, when the theme and characters of a play are simple and straightforward, is merely stupid.'

2. Radio Dramatists should be aware of the artistic principle of fading and cross-fading sound which is similar to the dissolve for cinema. '

3. Cross-fading' of parallel groups of voices is a most effective device, but it is extremely important that the voices should be sufficiently obviously different for there to be no confusion over the different sets of characters involved. Whilst casting of actors is the prerogative of the directors writers need to keep in mind the importance of writing 'effective differences' in characters - unless similarity is used as a specific plot device.

4. Gielgud's postulate: 'To sum up: the panel (like most machinery) is a good servant but a bad master.

5. He referred to the opening of 'Carnival' to explain the technique of writing to appreciate the process of sound mixing.

'In one studio Mr Compton Mackenzie was reading his opening narrative. As that reached its end the producer, by turning the knob on the panel, which controlled the strength of that particular studio, gradually faded the voice of the narrator to diminishing strength. Simultaneously, by turning in the opposite direction the knob which controlled the strength of the studio in which a barrel-organ was placed, he faded up the sound of the barrel-organ, which opened the first scene in the street where Jenny is dancing. As soon as the barrel-organ had been brought up to the requisite strength, i.e. the strength sufficient to stamp the background of the scene, it was faded down sufficiently to be background and nothing else. The producer then gave the 'light cue' to the actors, again in their separate studio, by pressing a switch which turned on a green light in the distant studio, and faded in their voices against the barrel-organ background, bringing them up to a strength at which they could be heard distinctly, though the barrel-organ continued to be faintly distinguished. There you have the use of three studios in proper operation.'

To what extent has the production of BBC Radio plays changed or transmogrified since 'turning knobs' and flashing 'cue lights'?

Apart from recording on location, pre-recording sequences and segueing them into live performance, the introduction of faders, multi-tracking and digital editing, it could be argued that the principles are roughly the same.

'The Wireless Play - V. June 21st 1929. People of the Play

1. Wireless dramatist must do his utmost to enable listeners to visualise characters in the imagination. The means at his/her disposal were:

a: strong and careful characterisation in dialogue.

b: simplicity in the human motives which go to make up the story.

2. Gielgud talked about 'fixing' the physical identity of characters and their background. Here Gielgud was laying the ground for what has been defined as the imaginative spectacle in audio drama. ( pp 53-69, Crook, T (1999) Radio Drama - Theory & Practice, London, New York: Routledge) He said: 'both eye and ear are merely a means by which you make an impression on the imagination of your audience.'

3. Gielgud was dismissive of the view that radio was an abstract medium dealing with purely abstract sounds. He argued that sounds without any interpretative significance were only a reductio ad absurdum of a practice. He lay down his cards with this view about the more experimental plays of Lance Sieveking and Tyrone Guthrie: 'How many of the people who heard 'Kaleidoscope The Second' could describe Sylvia's appearance or recognise her more personal characteristics? Deliberately or not, rightly or wrongly, Sylvia was a puppet. The interest of the audience was directed to the circumstances which swayed her life. They were, I think, completely unimpressed by the character of Sylvia the girl. Henry, in Squirrel's Cage, was better. At any rate, we knew that he stammered slightly. But he, too, and in the case I am quite sure it was deliberately done, ran too true to type to be real.'

The Radio Times art-deco illustration and listing for Lance Sieveking's 'The First Second' by Peter Godfrey. Not a play in the sense that it was described as 'A Sequence for Broadcasting'. Sieveking has been generally panned by academics and although heavily criticised during his time as a BBC producer should be accorded more value in terms of his courage and experimentation. The interiority of radio personality and consciousness lends itself to 'the subject matter of this drama - the beginning of the end of a man's life. The action occurs during the infinitely short space of time taken by sudden death to establish itself.'

4. Gielgud wanted greater care and greater emphasis in 'stamping... characters and... settings to further the easier working of the imagination of... listeners.

5. He said 'It is well known that people as a rule are not interested in other people that they do not know or have never met. Because you demand more of the imagination of your listeners than a writer for the stage, so you must provide that imagination with more material on which to work.

6. In the course of ordinary dialogue, the little personal idiosyncrasies are slipped in, or the most important features in a scene are underlined.

7. There is no doubt that people like to follow the experiences of characters whom they can understand, whom they can recognise among their friends, and at least some of whom they can like.

8. In 1929 Gielgud argued that Britain was 'not a cosmopolitan nation. The mentality of the average foreigner is a closed book to us'. He used this point to explain why the creations of Chekhov and Ibsen were regarded as 'quite simply lunatic.' It is a sign of xenophobia that was undoubtedly central to British culture at the time (When Britain was an Imperial/Colonial power) which some could justifiably argue remains pervasive among some people even today.

9: Aspiration to realism: Gielgud stated: radio drama should be fixed in the minds of would-be authors for the microphone as a drama of real people for real people. Preciosity has its place, but that place is not in radio drama.'

10. Gielgud recognised critical observations about the quality and standards of contemporary radio drama. Feminist writer Vita Sackville-West had written an article before stating 'it was necessary for a woman's voice to be alternated with a man's'. Early sign on concern about sexism and patronymic domination of the medium by male writers, directors and voices.

11. At the time Gielgud was emphasising the need for a special approach to microphone play writing; hence his comment: 'Except in so far that certain authors with a 'sense of the theatre' are also authors of fine intellectual attainment with a gift for writing dialogue and funds of ideas, their theatrical sense is immaterial.' [That the author of a radio drama should have a sense of the theatre is the very last thing that is necessary. A 'sense of the theatre' implies knowledge of one set of tricks; a sense of the microphone implies knowledge of another set of tricks.]

'Journey's End' had been a successful stage play in 1928 and 1929 and by the time of its first broadcast on Armistice day 11th November 1929 it had been performed in six different languages. It has had many BBC revivals and represents an excellent example of a theatre play which transfers effectively to the radio. The key may well be the psychology, characterisation and emotions which are highly charged and dramatised.

Gielgud provides an amusing account in 'Years of the Locust' of his struggle to persuade John Reith to permit the BBC to air 'Journey's End':

'There was an occasion when I found myself in his office pleading passionately for a performance of Journey's End as an appropriate commemoration of Armistice Day. I could not convince him. And as I remained persistent he passed me on to the Admiral. With the latter I waxed really eloquent, almost succeeding in reducing myself to tears in a mixture of emotion and baffled exasperation. I must have been there about quarter of an hour when Sir John looked in, and expressed surprise that I was still arguing.

"I don't understand what you want this play for," he said. "Anyone can write an appropriate programme for Armistice Day. I could write one - if I had the time. Of course you need a lot of guns and bells and things!"

And he disappeared before I could reply or comment. Again, it is only fair to add that ultimately I was allowed my own way, and was very handsomely congratulated for the success of the Journey's End production. I was perhaps fortunate in the fact that in Sir John's eyes the broadcasting of plays seemed rather a necessary evil, than a very serious branch of broadcasting activities.'

(p 70, Gielgud, V (1949) Years of the Locust, London & Brussels: Nicholason & Watson.)

In addition to an entire page given to the cast of the production and producer Howard Rose in the Radio Times included a photographic illustration of the set in the trenches - 'The Single Scene of 'Journey's End' and an appreciation of the play and its author by Charles Morgan.

The Wireless Play- VI. A Practical Example

(pp605 & 668, The Radio Times, June 28, 1929)

In his final article, Gielgud courageously exposes his inchoate radio dramatic career to potential attack by illustrating the main requirements of microphone drama with passages from an actual play-script which would appear to be his own script described as '"Exiles", a thrilling drama of the old Russia which may one day be heard over the microphone.'

He realised the risk he was taking:

'I am going to try to do the most difficult thing possible: to exemplify theory in practice.'

During the course of the article he exemplified the following techniques:

1: The climax of 'Exiles' 'has two good points: it keeps a 'high spot' of climax with an anticlimactic last line for its curtain - a purely theatrical but extremely effective device.'

2: The subject is' radiogenique - (a term recently coined in France, which may be translated as 'good radio'- on the analogy of 'good theatre') because it deals with people in circumstances which are certainly dramatic and which are not wildly improbable.'

3: The play has a definite contest between the attitudes of two minds towards the same problem. '...this argument which runs through the play serves in the place of narrative to link up and form a background to the whole piece.'

4: The two main characters bind the scenes together and lead up to them.

5: Gielgud acknowledges the value of rhythm and pace in structure: 'The play deals with a period which can only be reproduced by short scenes and against rapidly-changing backgrounds. Further, these backgrounds are in themselves picturesque.'

6: By providing the opportunity to switch scenes from the old Imperial Court, a St. Petersburg Cafe with a tsigane (gypsy) orchestra, and a dugout on the Galician Front, Gielgud says he is creating a production framework for introducing music 'as a strictly natural background to different scenes without having to force theme - or background - music purely for its own sake.'

7. 'Exiles' is a play which is impossible to stage and therefore conforms with the demand for drama which can only be handled through the wireless medium.

8: The script ensures that although there are a good many characters involved, only two have real personal significance. 'The others are mere shadows moving in a world of memories.' The cast is therefore small.

9: Gielgud does however acknowledge that a play which requires an orchestra, a tsigane orchestra, a chorus, and various straightforward sound effects is complicated. 'Exiles' is going to be a Savoy Hill five studio production. He justifies the elaboration without admitting that he is the author of the project with these words:

'A theme has deliberately been chosen which, to be properly exploited, requires these various expensive and complicated agencies, and these can be provided by the developing technique of the wireless play and could not by any other method.'

10: Gielgud claims that the author has done everything to serve 'clarity of treatment' by making his dialogue short and taut.

11: Gielgud also pays homage to influence. The scene subdivided into six sections to cover the stupendous episode of the Russian Revolution was inspired by the impressionistic methods of Tyrone Guthrie and Lance Sieveking. He says that Impressionism 'is one of the practising servants of radio dramatic technique. And the impressionist is in this case justified, because nothing else would serve to convey what is necessary for the development of the play by means of realism.'

12. Gielgud does not disclose a fundamental aspect of the play's motivation which is the special cultural and emotional knowledge and imperatives of the author. Gielgud and his family were a part of the world explored in the play. His relatives and his first wife were part of the 'White Russian' culture tossed about by the storms of Revolution and Empire.

Theorising and Prophesy

page 590 & 596, Radio Times, September 20, 1929

In the Radio Times edition for September 20th 1929 C.R. Burns attempted to predict the nature of Radio fifty years ahead to 1979. The justification for a somewhat Nostradamus approach to radio writing was provided by Eric Maschwitz with the words:

'Modern scientists seem to be agreed upon the theory, slightly stupefying to the average layman, that Space and Time are only figures of speech, and practically of no account. It is therefore without fear of reproach, on the score of improbability or fiction mania, that I add below an account flashed instantaneously to the Editor of 'The Radio Times' from his Special Correspondent at Geneva on August 15, 1979, for inclusion in the issue of that date....'

The article rightly predicted the BBC's survival in 1979 but wrongly anticipated a world of peace until that year with a celebration in a new Cathedral to peace at the old headquarters of the League of Nations in Geneva.

Burns rightly predicts a diet of news and market information for radio during breakfast time. He also correctly predicts the process of prerecorded programming which he describes as 'the great Gramophone Fusion.'

By 1960 he says that programmes will have been constructed, recorded, cut and edited upon the film model. To the extent that there is convergence on multi-track digital production techniques between the visual and audio media this has been achieved.

His optimism for the development of a huge library of programmes is partly fulfilled. Since archiving was not a contemporary practice in 1929 he was right to predict the collection of radio library examples of 'what are known as the first "Imperfect Classics" of the microphone, such as Mr Lewis's adaptation of Conrad's Lord Jim, Mr Berkeley's White Chateau, Mr Marvell's Carnival, and Mr Guthrie's Squirrel's Cage.'

The original broadcasts of these productions have not of course reached us but the Radio Drama conference at the BBC on January 13th 2001 would suggest that it was possible 'in the future' to experience 'revivals from what might almost be called the Stone Age of broadcasting are of the greatest interest, enabling listeners to compare the present with the dim and distant past.'

What was his prediction for radio drama 50 years in the future in 1979 and to what extent was it realised?

'Unfortunately, I have no space left in which to describe the latest developments in radio drama with its twenty-five studios or the new effects room with its electrically-controlled mechanism enabling anything from the Deluge to the Battle of the Trafalgar or Beethoven's Ninth Symphony to be used severally or in combination merely by the turning of one or more switches. Nor can I enter here into the great current controversy as to whether English is to be adopted as the international radio language, though I am informed that this development is bound to occur in the course of the next five years owing to the preponderating pressure of the whole of the American group, taken together with the influence that English traditions have maintained upon the European group.'

There is a certain excitement in recognising that this writer had correctly imagined the eventual advances in manipulating a multi-dimensional synthesis of sound through digital technology. The power he describes in 1979 was available to the radio producer in the analogue form in that year, and now that power has been extended digitally. And the BBC certainly had access to 25 studios in 1979 but there was no need for all to be used at the same time for the purposes of a dramatic production. He is also correct about the global power of English as the international media language and he correctly links this to the likely influence and role of the USA in world affairs. Finally it could not be ruled out that C. R. Burns was Eric Maschwitz himself since the idea of the correspondent was fictional and it was well known that he would fill holes in the magazine with articles by himself which were attributed to various pseudonyms.